Contents

Introduction

Chapter I. Historical Sketch

Chapter II. Personal Testimony

Chapter III. Mind And Disease

Chapter IV. Quimby’s Theory of Man

Chapter V. The First Teachers

Chapter VI. The Omnipresent Wisdom

Chapter VII. The Power Of Thought

Chapter VIII. Spiritual Healing

Chapter IX. Methods Of Healing

Chapter X. Summary and Definition

Introduction

There are three general points of view from which one may regard the mental life of man in its relation to the body. In the first place, the mind may be regarded from below, as if it were a mere product of matter. From this point of view, every event in man’s mental history is a result of physical processes; every thought, feeling, or volition springs from, and is dependent upon certain conditions of the brain. What is called “consciousness” is a product or accompaniment of bodily life; matter alone is ultimately real; mind has no significance apart from it. The “soul” is an invention of human thought, devised to account for the higher phases of cerebral productivity. This is the point of view of typical old-time materialism.

From the second point of view, mental states and bodily processes are regarded as if they existed on the same level. This may mean that physical events are taken to be merely parallel with psychic states, with no interchange. Or, it may imply belief in the interaction of mind and brain. Biologically speaking, it involves a theory of mental development corresponding to physical evolution. Most scientific theories of the relationship of mind and matter belong under this head. In some respects it is also the point of view of popular thought.

In the third place, the observer is supposedly located within the mental life, looking out through “the windows of the soul” upon all the world. This position is not explicitly the point of view of any recognised school of thought, yet it is implied in many popular and unscientific beliefs. It is also the standpoint of those who maintain that the brain is merely the physical instrument of the soul. Such a position need not imply the complete independence or supremacy of the soul. But it may reasonably include the conviction that, on occasion, the soul is roused into masterful activity and is thereby enabled to initiate new lines of action. Many works of genius and occasional triumphs of the will seem to imply that the soul is superior, not merely as an observer of the bodily life going on below, but as an actual master of adverse conditions. Inspired by the study of such instances, contemporary theorists frequently point out that man is a soul with a body, not a body with a soul. It is even said that the soul is potentially master of every portion of bodily life, that in the long run the body becomes what the soul makes it.

Whatever one may think of the extravagant and other unscientific beliefs which belong under this head, it is clear that both for theoretical and for practical purposes every one should be able to take up the position from which the body and the entire physical world are looked at from above. When we pause to think, we are compelled to admit the existence of consciousness as the primal and surest fact. What we know of the great world around is known through our states of consciousness, and if we seem to be living a merely objective life, amidst external things, it is because we have become oblivious of the real nature of experience. We live in the inner world of our own mental life, contemplate, reflect, and react upon events which, as known by us, are purely mental. Hence the burden of proof rests upon the materialist, not upon the idealist. If it requires thought to discover that we live fundamentally a mental life, the result of our analysis is the discovery that no point of view is more natural than that of the outward look from within.

It is one thing, however, to start with the fundamental fact of consciousness and arrive at idealistic conclusions about human experience as a whole, and another to regard the inner life as the centre of practical activity. The theoretical discipline is highly profitable. It is well to remind ourselves many times that in very truth we lead a conscious life. But as idealism in theory is not necessarily idealism in practice, a much severer discipline is needed before one is in a position to test the optimistic popular beliefs in regard to the supremacy of the soul No one is ready to test these beliefs to the full who is unwilling to regard the soul as potentially a master. Now that materialism has had the fullest hearing, it is but fair that a distinctly spiritual point of view should have recognition. Most men have a half-dormant conviction that they have never accomplished what they might by mental power. Mere theory is of no avail in this connection: each man must investigate his mental world, experiment with his own mind. The chances are that every man will confess with shame that he even lacks the first requisite, namely, self-control.

A simple illustration will show the difference between the man who is at home in his mental world and the one who is without inner resources. Let it be a typical case of the approach of sudden illness, or simply the presence of a slightly painful sensation with which the mind unwittingly associates the name of a dreaded disease, with all its terrors. The man who has no staying power, no knowledge of his inner self, is swept forward by the consciousness of sensation, a description of which he communicates to a physician, who in turn is compelled to judge the case from the outside. By skilful questioning, many doctors are indeed able to work their way, as it were, well into the interior of a patient’s life. Yet all this is relatively external. Even in cases of so- called mental disease the physician very naturally judges the mental states by their physiological conditions. Important as this judgment may be, there is still another story to be told.

On the other hand, let it be a case where the person in question is in some measure aware of the resources of the inner life. External aid may or may not be necessary. The symptoms may or may not be alarming. But if there is a tendency towards emotional excitement and fear, with their bodily accompaniments, these tendencies are inhibited, met with calmness and self-control. The person in question may not be able to follow up the advantage and actively overcome the disease by mental methods. But many people know from experience what it is to inhibit the rising tide of emotion which so soon passes beyond control if not stopped at once. Let this suffice in a general way for an illustration of the third attitude towards our mental life.

It is clear that no theory of the inner life can long stand which ignores any of the facts involved in the three attitudes above described. There is no need of assertion of mental power, or denial of the reality of matter, if one possesses the facts. Yet as the most important facts are those of which we know least, there is need of searching investigation into the obscurer regions of the inner life, that we may be able to weigh the evidence for and against the most sharply contrasted points of view. It would be excusable if for a time no facts should be considered except those which indicate the supremacy of mind.

The purpose of this book is to bring these neglected considerations into view. By the term “inner life,” as here used, is meant the mental experience of man in so far as it involves practical beliefs and active attitudes. The inner life is the series of psychic states which each of us discovers as a unique, individual possession. In its outer references, our inner life is related to the great world of things and persons. Within its own precincts, it involves references to the dimly conscious, the subconscious, to an underlying selfhood, and to ultimate reality, or Being. It is with the less-known phases of the inner life that we are to be concerned, and always the point of view will be that of the observer or participant, looking out upon life from within.

By the term “health” is meant not so much the bodily condition as the accompanying mental states. In the larger sense of the word, health means a sound mind in a sound body. This being so, it is necessary to study the problems of health and disease as affairs of the entire individual. But every one is supposed to understand the conditions of physical health, or at least to know where to obtain the necessary information; the real problem is to discover the hidden factors on the mental side of life. To become conscious of the inner life in its relation to health is to learn what manner of life one lives at large, then to discover the central sources of conduct in so far as conduct comes within the province of the will. The science of physical health may be acquired in a more general way. The science of mental health springs out of an art of life which each individual must acquire through far more intimate self-knowledge than the average man possesses.

Let us assume, then, that the reader has taken up the subjective position above characterised, and that he is prepared to test the teachings of this book by direct reference to experience. Mere theory is of so little consequence in our undertaking that scarcely a statement can be weighed apart from instances which exemplify the power of mind, together with the study of personal problems of health. It matters little how far the individual problem has been carried. The art of health is still an ideal for most of us. Numbers of people have reached the point where they clearly see that health is part and parcel of the art of life. The essential is to begin wherever each of us stands and consider how to take the next step. That no merely physical solution of the problem is possible is perfectly clear. But that the true mind cure demands wise thought for things of this life is no less plain. Whatever the conclusion, it is clear that the art of health is the art of common sense. Not even while one is bringing the hidden factors of mind to the fore is one called upon to neglect the wisdom of the past in regard to the conditions of physical existence. If one is to triumph over the ills of the flesh and the woes of the mind it must be by full acknowledgment of the actual facts of real life. The theorist who believes in affirming the supremacy of mind at all costs is likely to take slight interest in this book.

It is not necessary to begin a new series of experiments in order to have data for our present inquiry. The experiment has been in process for more than half a century, and actual life is more fruitful than artificial experiment.

One can scarcely raise the question, how far the mind has power over the body, without a reminder that a mind-cure movement has existed for many years. It is hardly possible to discuss the question without first reckoning with that movement, for otherwise it will be assumed that one accepts all sorts of beliefs to which one takes the most decided exception. Moreover, there are particular reasons for prefacing the present inquiry with an historical introduction. The reasons will become apparent as we proceed.

Twenty-five years ago, when the mental-healing movement was first publicly discussed, it was lightly put aside as “the Boston craze,” and an early death was prophesied for it. Consequently no attempt was made to sift the wheat from the chaff, no record was kept of instances of cure. Since that time, the movement has attained large proportions, and has repeatedly divided and subdivided. At one time there were three so-called international societies holding independent conventions for the discussion of mental-healing theories. More than one hundred publications have been issued for brief periods, sixty of which were in existence at one time. The output of books has run into the hundreds, and while the majority contain repetitions of a few ideas many have had a large sale. Little “centres of truth” independent churches, and metaphysical clubs have been established here and there throughout the English-speaking world. The practice of mental healing has grown steadily, and both physicians and clergymen have felt the results of widespread adherence to mind-cure doctrines. The tendency has been to make a religion of the cult, to substitute it both for current forms of worship and for medical practice. Entirely aside from the hold which its most radical form has had upon the community, many people have now come to the conclusion that the general doctrine has come to stay and must be reckoned with.

Some of the claims of mental-healing devotees are enormously extravagant, and certain phases of the general movement are decidedly ephemeral. Has the time come when it is possible to estimate its more permanent phases, and evaluate the practice of mental therapeutists? There are reasons for believing that such an estimate is now possible. The output of publications reached its height about four years ago. New books on mental healing are published now and then, but they add little to the general doctrine. There is a tendency on the part of the public to assimilate the sounder notions and reject the specialisms. Hence it is easier to see what ideas and methods are likely to prove of permanent value.

In order to prepare the way for the assessment of existing mind-cure doctrines, it is important to reconsider the parent theory out of which the present-day beliefs were differentiated. The general doctrine was much simpler when it was first promulgated, and the first books on the subject are among the best that have been written. Whatever the value of the general theory as originally set forth, it was given a direction which it has ever since followed, and to understand the present tendencies one must trace their history. Again, there is need of such a study because most of the writers have been inclined to ignore their own indebtedness. Usually when the history of the subject has been referred to, it has been in a controversial spirit. Hence the significance of the original discoveries has been overlooked.

As a contribution to the scientific investigation of the whole field, the present volume is intended to inform rather than to convert. With this aim in view, it has seemed best to reconstruct in one volume various articles and portions of earlier books, so that the original theory might be appreciated on its own merits. Hitherto there has been no book of this character, because most of the writing under this head has been didactic or dogmatic. Mental-healing writers as a rule take little interest in facts. As opposed to this general tendency, the mind-cure theory of the future will be reared on facts. If dispassionate inquiry shall some time take the place of exaggerated assertion, the future history of the doctrine will be strikingly in harmony with its pioneer stages.

Entirely aside from the possible values of present-day mind-cure theories, this volume is issued with the conviction that there is a phase of the general doctrine which has received little recognition, even in this day of unprecedented interest in such therapeutic systems. Every one knows something about “Christian Science” Having heard about the malpractice which occurs in connection with that doctrine, and having condemned the whole theory as absurd, the tendency has been to classify allied doctrines under the same head. To broach any subject that resembles mind-cure theory is forthwith to be relegated to the domain of the unbalanced, and hence to be scornfully denied a hearing. It is easy to preach against the whole theory, as thus publicly scorned. On the other hand, it seems never to occur to the critics that there may be a theory which has little in common with the one which has been condemned. Many exposures of “Christian Science” have been published, but not one has gone to the root of the matter; hence every exposure has added fuel to the flames.

There would be two rational methods of exposing “Christian Science” and its offshoots. One plan would be to make a thorough study of the facts of mental-healing practice. In this way one might assimilate all that is therapeutically sound, although the religious and metaphysical aspects of the theory would require separate consideration. The other method would be to seek the facts in regard to the early discoveries of mental healing, examine the inferences drawn from those discoveries by the founder of “Christian Science,” and select the sound from the unsound. For the best way to understand an error is to discover its genesis. All this by way of suggestion to would-be destroyers of the doctrine.

We are reminded, however, by wise men like the late Professor Joseph Le Conte that “pure unmixed error does not live to trouble us long” The fact that the rational mind-cure theory has survived more than fifty years is proof that it contains truth. The fact that the earlier form of the doctrine is the one that has been clung to most persistently by the class of people who make no noise in the world should be no less significant. But even “Christian Science” has played its part in our time. Hundreds of the more rational mental-healing exponent began as devotees of that doctrine which, with all its extravagances, at least served to awaken them from “dogmatic slumbers.”

From the point of view of the more rational mind-cure theory, nothing could have been more unfortunate, however, than the undue emphasis which has been put upon “Christian Science” The rational investigation which the whole subject demands has been kept back a score of years on account of it. Yet at any time during the last decade, to investigate would have been to discover that the mind-cure movement has come to stay, and to conclude that the best course to pursue is to search out the truth and cease to denounce the error. No remedy is so effectual as truth. A tithe of the energy which has been spent in denunciations would have served to bring out the vital truth. The real fact to explain is not the “psychological moment” namely, the flocking of the multitude into “Christian Science” churches, but the fact of mental cure. If it were not for the cures which have somehow been wrought, the churches would never have been built. A spirit of genuine religion has also worked its way in. But the explanation of this fact belongs with the other. It is the peculiar connection of health with religion that constitutes the strangeness of the phenomenon. It is an interesting fact that the only person of great scholarly repute who has ever paid the mind- cure movement any serious attention seized upon its religious aspect as its practical essence.[1]

The peculiarity of a doctrine which thrives upon its practical characteristics is that it appeals at first only to those who have experienced its benefits. All the pioneers of the mental-healing movement were restored invalids, and all the leaders since the early days have been restored to health under mental treatment. The mental-healing belief has forthwith become a metaphysic and a religion, but the prime interest was therapeutic. It was by restoring himself to health that P. P. Quimby, the parent mental healer in this country, discovered the central principles of the whole doctrine. The first mental- healing author, W. F. Evans, was a patient of Mr. Quimby before he began to write upon the subject. The same is true of the author of Science and Health.

Whatever one’s intent, then, whether it be to refute the error or to assimilate the truth, one should begin at the beginning, and endeavour to understand the theories which have meant so much to the pioneer devotees.

The present discussion is intended both for the scientific student and for the practical man. Those who wish to understand the mental-healing methods will be able to select the principles which appeal to them by following the historical development of the general doctrine. On the other hand, those who are inclined to expose the whole teaching may perhaps be able to discover the first flaw in Mr. Quimby’s reasoning, by collecting and comparing the quotations from his manuscripts which appear here and there in this volume.

Those who read deeply will doubtless discover the truths which have caused the mind-cure movement to live. To study the original teachings is to be convinced that they sprang out of genuinely human experience. No one can judge the teachings fairly who judges by the letter alone. The early devotees were filled with zeal for practical truths; they were eager to help suffering humanity. They sometimes failed to say what they meant. But every one who reads sympathetically will see that their faith is susceptible of practical application, hence that the record of experience is often of more value than the theory which is brought forward to account for it.

As contrasted with later forms of mental-healing theory, the tendency of the parent doctrine is to place emphasis upon understanding, rather than upon denial and affirmation. Mr. Quimby sought above all else to discover man’s actual situation in life, then to see the wisdom of that situation. He made no attempt to deny the existence of the natural world, but sought its meaning in relation to the spiritual. Nor did he ignore the physical conditions of disease, well knowing that they are decidedly real to the person who is subject to them. His interest was to penetrate beneath the surface to the interior mental and spiritual causes. Any fact that might throw light on the inner conditions was to be welcomed. Hence the tendency of his thought was not to exclude but to analyse and to master, not to deny but to explain. Mr. Quimby was eager to follow the truth wherever it might lead, firm in the conviction that when discovered it would set man free. His own experience and insight had brought into view a more interior series of facts. On these he believed it possible to rear a truer science and art of life. It is this scientific interest, together with the profounder spiritual principles which it implies, which has been lost sight of during the reign of recent forms of mind-cure teaching. Were it not for this deeper interest many devotees of the movement would have had no connection with it. To approach the subject in this spirit is to put the whole teaching in a different light, to see that it is essentially rational, after all. At the same time one sees why the dozen or more variations have developed from the original teaching by putting emphasis on certain favourite considerations.

There are a number of questions which occur to the mind when the mental-healing theory is brought forward in all seriousness. To inquire into the issues thus raised is to find the clue to the permanent interests which have made the mind cure possible. For example, the question arises, What is meant by saying that disease is largely of mental origin? How is it possible to alleviate or cure suffering by sitting silently beside a patient? How does it happen that the facts of mental cure lead the person who is restored to health to take profound interest in psychology and philosophy? Why is the mode of life changed? Why should one connect the healing of disease with religion?

It is with such questions that the present volume is concerned. The best result that can come to the reader will be the discovery that he is in the midst of a new investigation. Some of the earlier statements will be found of little permanent value. Their importance lies in the fact that they exhibit the clues which earnest souls have actually followed in the pursuit of truth. Hence the essential is the implied point of view. To realise even in some slight measure the significance of that point of view is to see that it has direct bearings upon everything that most intimately concerns the soul.

Chapter I. Historical Sketch

From one point of view, the mind cure is as old as human belief. For if there is any efficacy in the objects with which superstition clothes itself, that power is found in man’s belief in invisible agencies. Primitive beliefs were animistic. Man projected his own emotions and thoughts into the visible world. He sought to adjust his conduct so as to take advantage of supernatural powers. Very early there appeared a belief that disease could be cured by various occult practices. Works on anthropology, such as Tylor’s Primitive Culture, abound in accounts of strange notions about sickness as supposedly caused by the partial maladjustment of the soul to the body, or to some other unusual mental condition, while peculiar beliefs about the efficacy of the mind are no less common. To this day, so the anthropologists assure us, there are savage peoples who believe that distant members of the tribe may be telepathically influenced. The principle that “like affects like” is common to both ancient and modern mind cure. For example, an act performed upon a certain part of the body is supposed by some savage peoples to produce a corresponding effect upon an absent individual. In some tribes it has been the custom for the wives of the distant warriors to gather round the fire at home and put themselves through the operations which their liege lords were supposed just then to be going through, and hence to aid them to conquer.

There is scarcely a tenet in the mind-cure faith of to-day that cannot be paralleled by a corresponding belief in ancient or savage times. In all ages and among various peoples there have been periods when belief in unusual powers have been prevalent. Many would set these down as outbreaks of credulity. Others would say that the race will be subject to such attacks until their law is understood, their meaning and truth assimilated. At any rate, these strange upheavals of all that is occult and weird are of peculiar interest to the mind-cure devotee, for they show that there has been a very general yearning after the knowledge which our age, at last, is likely to discover. Now that societies for psychical research exist, and scientific hypotheses concerning the subliminal region have been proposed, we are likely to assimilate the truth and discard the superstition. If our age has witnessed a more violent outbreak than the attacks of superstition which have visited other times, the meaning probably is that we now have the scientific weapons wherewith to meet it. In the future there will perhaps be no need of special sects for the promulgation of such beliefs, for there will be a science of all such phenomena.

In India, where science has not been distinguished from superstition as we would discriminate, the age of belief in unusual powers has been practically continuous. The literature of Buddhism is particularly rich in doctrines which the mind-cure devotee of to-day has restated. In the Dhammapada, Buddha gives utterance to a sentence which might well stand for the modern theory oddly denominated the “New Thought” Buddha says: “All that we are is the result of what we have thought; it is founded on our thoughts, it is made up of our thoughts” Every student of the Vedas and Upanishads knows that these Hindoo sacred books abound in statements which are almost identical with recent mind-cure sayings. In the Maitrayana Upanishad it is said that “thoughts cause the round of a new birth and a new death… .What a man thinks, that he is: this is the old secret”2

In the least-known and speculatively less important Atharva-Veda there are suggestions and affirmations for the cure of disease which rival in minuteness and number any modern mind-cure scheme. There are special charms to cure fever, headache, cough, jaundice, colic, heart disease, paralysis, hereditary disease, leprosy, scrofula, ophthalmia, and dozens of other diseases. There are affirmations to overcome the effect of poison, to procure easy childbirth, to conquer jealousy, to control the kind of offspring, even to obtain a husband or secure a wife. The modern devotees of “claims” for success have been anticipated by the authors of this Veda, who also point out how one may “attract” prosperity. Even the charm for obtaining long life is given. Again, the principle is recognised that people who have little faith must eke out their faith by the use of material means. Here, for instance, is a suggestion to be made when one partakes of spring water to aid in carrying off foreign matter from the body: “The spring water yonder which runs down upon the mountain, that do I render healing for thee, in order that thou mayest contain a potent remedy” It is clear that the ancient sages understood all the secrets of the mind cure. For untold ages the “New Thought” has been old in India.

Turning to Plato, one finds many hints that might be developed into mind- cure theory of the more rational type. Plato maintains that many of our ills and diseases are due to excess. He complains that certain kinds of medical practice tend to increase the number of diseases, and points out that people become invalids through failure to learn the lesson of their indiscretions. Temperance, moderation, balance, self-control, or order within—these are the remedies which Plato proposes. But for Plato no normal development of the soul is possible without the cultivation of the body. A sound mind in a beautiful body is his ideal. One who should take Plato’s Republic for his practical guide might well dispense with most of the modern mental-healing theories.

Again, in the teachings of the Epicureans, the Stoics, and Sceptics, there are ideas and methods which remind one of current doctrines. The age of Greek practical philosophy was a period of belief in equanimity, inner peace, freedom from external disturbance. The first stress was put upon the inner life, and the philosopher practised what he taught by maintaining a wise attitude towards life. The relation of this attitude to bodily health apparently did not concern the philosopher of that day. Nevertheless, some of the essentials were known, and the benefits of the philosophic mode of life were experienced. It has remained for us to trace the connection between inner peace and bodily benefits.

Through the middle ages there were outcroppings of doctrines and practices which still more closely resemble recent teachings. Instances of remarkable healing were more common than in earlier periods. Some of the later idealistic philosophers came very near the application of their philosophy to health. Again, in Spinoza’s Ethics there are suggestions of mind- cure doctrines. The lives of philosophers such as Kant afford considerable material for reflection to all who are interested in the connection between physical health and the inner life. Just previous to and contemporaneously with the first mind-cure investigations in America, interest in what was then called “mental hygiene” began to appear here and there, and a number of books were written on the subject. There are also some points of resemblance between the later mind-cure teachings and the theories of The Philosophy of Electrical Psychology, by John Bovee Dods.[2]

When all has been said, however, it is beyond dispute that it remained for a man who knew almost nothing about the teachings of the past to make the investigations which in due course led to the development of what we now know as mental healing. Now that we possess the theory, it is of course easy to find confirmatory evidences all through the ages, and allied interests in the nineteenth century. It is but fair, however, to acknowledge the work which really made the mind-cure movement possible, and, if any credit is given, assign it to the one who really deserves it. The movement sprang, directly or indirectly, from the work of half a dozen persons, all of whom were healed by the pioneer mental therapeutist of America. Many have enjoyed the after-benefits who have never heard of this pioneer. But that does not alter the fact that in a peculiar way their beliefs are bound up with the history of the movement.

The history here narrated is not told for the sake of exalting a personality, but because the facts bear upon the teachings in question. In our time, it is well understood that theorist and theory are inseparable. If we would rightly understand a doctrine which has taken firm hold of the people we must know how it arose in the life of the one who propounded it. To insist that it came “by revelation” is nowadays no explanation. To put forth only such statements as chance to please their promulgator is to create an illusion which must some day be exposed. The well-informed know that every truth has had a long history. Truth and error are alike bound up with personal incidents which otherwise may be of slight consequence.

Few men have begun and carried on an investigation in a more humble and quiet way than Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, who was born in Lebanon, New Hampshire, February 16, 1802, and died in Belfast, Maine, January 16, 1866. When he was two years of age, his parents moved to Belfast, where he lived until his death, except during the busier years of his practice in Portland, Maine. His father was a blacksmith, and he was one of a family of seven children. On account of his father’s scanty means, and because of the meagre educational opportunities at hand, his schooling was very limited. During his boyhood he attended the town school a part of the time, and there he acquired a knowledge of the rudimentary branches. His training was obtained for the most part, however, in the school of experience. He greatly regretted that his education had been so meagre, but the lack of it was plainly his misfortune and was not due to any defect on his part. In later years, when the desire came to familiarise himself with the philosophical teachings of the past, his life was too full to permit it. His son, George A. Quimby, who is the authority for the facts here given,[3] says that “he had a very inventive turn of mind, and was always interested in mechanics, philosophy, and scientific subjects. During his middle life he invented several devices, on which he obtained letters patent. He was very argumentative, and always wanted proof of anything rather than an accepted opinion. Anything that could be demonstrated he was ready to accept; but he would combat what could not be proved with all his energy rather than admit it as a truth.”

With a mind of this type, it was natural that when Charles Poyan, a Frenchman, introduced mesmerism into this country, about 1836, and later gave lectures and made experiments in Belfast, Mr. Quimby should become greatly interested. Here was a phenomenon that to him was entirely new and worthy of investigation. Accordingly he at once began to inquire into the subject, and whenever he found a person who was willing to be experimented upon he would try to induce the mesmeric sleep. He frequently failed, but now and then found some one whom he could influence.

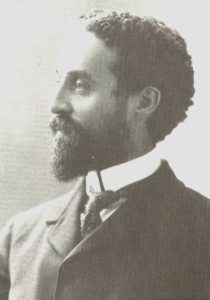

“At that time Mr. Quimby was of medium height, small in stature, his weight about one hundred and twenty-five pounds; quick-motioned and nervous, with piercing black eyes, black hair and whiskers; a well-shaped, well-balanced head; high, broad forehead, and a rather prominent nose, and a mouth indicating strength and firmness of will; persistent in what he undertook, and not easily defeated or discouraged.[4]

“In the course of his trials with subjects he met a young man named Lucius Burkmar, over whom he had the most wonderful influence; and it is not stating it too strongly to assert that with him he made some of the most astonishing exhibitions of mesmerism and clairvoyance that have been given in modern times.

“At the beginning of these experiments, Mr. Quimby firmly believed that the phenomenon was the result of animal magnetism, and that electricity had more or less to do with it. Holding to this, he was never able to perform his experiments with satisfactory results when the ‘conditions’ were not right, as he believed they should be. For instance, during a thunder-storm his trials would prove utter failures. If he pointed the sharp end of a steel instrument at Lucius, Lucius would start as if pricked by a pin; but when the blunt end was pointed toward him, he would remain unmoved.

“One evening, after making some experiments with excellent results, Mr. Quimby found that during the time of the tests there had been a severe thunder-storm; but, so interested was he in his experiments, he had not noticed it. This led him to further investigate the subject; and the results reached were that, instead of the subject being influenced by any atmospheric disturbance, the effects produced were brought about by the influence of one mind on another. From that time he could produce as good results during a storm as in pleasant weather, and could make his subject start by simply pointing a finger at him as well as by using a steel instrument.

“Mr. Quimby’s manner of operating with his subject was to sit opposite him, holding both his hands in his, and looking him intently in the eye for a short time, when the subject would go into that state known as the mesmeric sleep, which was, more properly, a peculiar condition of mind and body, in which the natural senses would or would not operate at the will of Mr. Quimby. When conducting his experiments, all communications on the part of Mr. Quimby with Lucius were mentally given, the subject replying as if spoken to aloud.

“For several years Mr. Quimby travelled with young Burkmar through Maine and New Brunswick, giving exhibitions, which at that time attracted much attention and secured notices through the columns of the newspapers.

“It should be remembered that at the time Mr. Quimby was giving these exhibitions, over forty-five years ago,’ the phenomenon was looked upon in a far different light from that of the present day. At that time it was a deception, a fraud, and a humbug; and Mr. Quimby was vilified and frequently threatened with mob violence, as the exhibitions smacked too strongly of witchcraft to suit the people.

“As the subject gained more prominence, thoughtful men began to investigate the matter, and Mr. Quimby was often called upon to have his subject examine the sick. He would put Lucius into the mesmeric state, who would then examine the patient, describe his disease, and prescribe remedies for its cure.

“After a time Mr. Quimby became convinced that whenever the subject examined a patient his diagnosis of the case would be identical with what either the patient himself or some one present believed, instead of Lucius really looking into the patient, and giving the true condition of the organs; in fact, that he was reading the opinion in the mind of some one, rather than stating a truth acquired by himself.

“Becoming firmly satisfied that this was the case, and having seen how one mind could influence another, and how much there was that had always been considered as true, but was merely some one’s opinion, Mr. Quimby gave up his subject, Lucius, and began the developing of what is now known as mental healing, or curing disease through the mind. In accomplishing this he spent years of his life fighting the battle alone and labouring with an energy and steadiness of purpose that shortened it many years.

“To reduce his discovery to a science, which could be taught for the benefit of suffering humanity was the all-absorbing idea of his life. To develop his ‘theory,’ or ‘the truth,’ as he always termed it, so that others than himself could understand and practise it, was what he laboured for. Had he been of a sordid and grasping nature, he might have acquired unlimited wealth; but for that he seemed to have no desire.

“In a magazine article it is impossible to follow the slow stages by which he reached his conclusions; for slow they were, as each step was in opposition to all the established ideas of the day, and was ridiculed and combated by the whole medical faculty and the great mass of the people. In the sick and suffering he always found staunch friends, who loved him and believed in him, and stood by him; but they were but a handful compared with those on the other side.

“While engaged in his mesmeric experiments, Mr. Quimby became more and more convinced that disease was an error of the mind, and not a real thing; and in this he was misunderstood by others, and accused of attributing the sickness of the patient to the imagination, which was the reverse of the fact. No one believed less in the imagination than he. ‘If a man feels a pain, he knows he feels it, and there is no imagination about it,’ he used to say.

“But the fact that the pain might be a state of the mind, while apparent in the body, he did believe. As one can suffer in a dream all that it is possible to suffer in a waking state, so Mr. Quimby averred that the same condition of mind might operate on the body in the form of disease, and still be no more of a reality than was the dream.

“As the truths of his discovery began to develop and grow in him, just in the same proportion did he begin to lose faith in the efficacy of mesmerism as a remedial agent in the cure of the sick; and after a few years he discarded it altogether. Instead of putting the patient into a mesmeric sleep, Mr. Quimby would sit by him; and, after giving him a detailed account of what his troubles were, he would simply converse with him, and explain the causes of the troubles, and thus change the mind of the patient, and disabuse it of its errors and establish the truth in its place; which, if done, was the cure. He sometimes, in cases of lameness and sprains, manipulated the limbs of the patient, and often rubbed the head with his hands, wetting them with water. He said it was so hard for the patient to believe that his mere talk with him produced the cure, that he did this rubbing simply that the patient would have more confidence in him; but he always insisted that he possessed no ‘power’ or healing properties different from any one else, and that his manipulations conferred no beneficial effect upon the patient, although it was often the case that the patient himself thought they did. On the contrary, Mr. Quimby always denied emphatically that he used any mesmeric or mediumistic power.

“He was always in his normal condition when engaged with his patient. He never went into a trance, and was a strong disbeliever in spiritualism, as understood by that name. He claimed that his only power consisted in his wisdom, in his understanding of the patient’s case, and his ability to explain away the error and establish the truth, or health, in its place. Very frequently the patient could not tell how he was cured; but it did not follow that Mr. Quimby himself was ignorant of the manner in which he performed the cure.

“Suppose a person should read an account of a railroad accident, and see, in the list of killed, a son. The shock on the mind would cause a deep feeling of sorrow on the part of the parent, and possibly a severe sickness, not only mental, but physical. Now, what is the condition of the patient? Does he imagine his trouble? Is it not real? Is his body not affected, his pulse quick; and has he not all the symptoms of a sick person, and is he not really sick? Suppose you can go and say to him that you were on the train, and saw his son alive and well after the accident, and prove to him that the report of his death was a mistake. What follows? Why, the patient’s mind undergoes a change immediately, and he is no longer sick.

“It was on this principle that Mr. Quimby treated the sick. He claimed that ‘mind was spiritual matter, and could be changed’; that we were made up of ‘truth and error’; that ‘disease was an error, or belief, and that the truth was the cure.’ And upon these premises he based all his reasoning, and laid the foundation of what he asserted to be the ‘science of curing the sick’ without other remedial agencies than the mind”

Very much has sometimes been made of the fact that Mr. Quimby was once a mesmerist, and some have contended that he was never anything more. The simple facts are that mesmerism afforded him an opportunity to discover his own powers, and that when he saw the significance of mesmeric phenomena he discarded both the theory and the practice. This was years before his public work as a mental healer. That this was the case, the following quotations also show. In a lecture delivered in Boston, in 1887, at the request of those who wished to know about Mr. Quimby,[5] Julius A. Dresser said:

“The first that I knew of P. P. Quimby was in June, 1860, when I went to him as a patient, in Portland, Maine. This was five and a half years before his death. He had then been in the regular practice of mental healing for many years, in different towns in Maine, and had been located in Portland about two years. There was at that time, 1860, no one else in the practice in New England or in this country; nor was there at that time any one else who understood it as a science, he having been the discoverer and founder. He had then been at work more than twenty years in this field of discovery and practice.

“The question may be asked, Was Quimby ever a mesmerist? I reply that he was, for a limited time, and for purposes of experiment and investigation. The truth came to him, not as a revelation pure and simple, but as the result of practical experiment and patient research, urged on by the impulses of an active, inquiring, comprehensive mind. I have seen extracts from newspapers as far back as 1842-43, giving accounts of his public exhibitions of mesmerism, in some of which he was rated with a few others in this country and Europe who were the leading mesmerisers in the world….

“In his mesmeric experiments, as reported in the Maine papers in those years so long ago, Quimby is shown to have progressed gradually out of mesmerism into a knowledge of the hidden powers of minds. He soon found in man a principle, or a power, that was not of man himself, but was higher than man, and of which he could become a medium. Its character was goodness and intelligence, and its power was great. He also found that disease was primarily an erroneous belief of mind. Here was a discovery of truth; and on this discovery he founded a system of treating the sick, and founded a science of life.”

In a circular addressed to the sick, Mr. Quimby thus described his own system:

“My practice is unlike all medical practice. I give no medicine, and make no outward applications. I tell the patient his troubles, and what he thinks is his disease; and my explanation is the cure. If I succeed in correcting his errors, I change the fluids of the system and establish the truth, or health. The truth is the cure. This mode of practice applies to all cases.”

Commenting on this specific statement, Mr. Dresser continues:

“These are Mr. Quimby’s own words, and any one can see that they mean a purely mental treatment; for he speaks of what the patient thinks is his disease, and calls it his error, by saying that, if he succeeds in correcting the patient’s errors, he then establishes the truth, and the truth is the cure. You see from this that he had discovered that disease was due to an error of mind, and the God-power of truth which he had discovered in man, being set up again in the victim of disease, destroyed the error, or disease, and re-established the harmony.

“This discovery, you observe, was not made from the Bible, but from the study of mental phenomena and as the result of searching investigations; and, after the truth was discovered, he found his new views portrayed and illustrated in Christ’s teachings and works. If you think this seems to show that Quimby was a remarkable man, let me tell you that he was one of the most unassuming men who ever lived; for no one could well be more so, or make less account of his own achievements. Humility was a marked feature of his character (I knew him intimately). To this was united a benevolent and an unselfish nature, and a love of truth, with remarkably keen intuitive powers. But the distinguishing feature of his mind was that he could not entertain an opinion, because it was not knowledge. His faculties were so practical and intuitive that the wisdom of mankind, which is largely made up of opinions, was of little value to him. Hence the charge that he was not an educated man is literally true. True knowledge to him was positive proof as in a problem of mathematics. Therefore, he discarded books and sought phenomena, where his intuitive faculties made him master of the situation. Therefore he got from his experiments in mesmerism what other men did not—a stepping-stone to a higher knowledge than man possessed, and a new range to mental vision”[6]

But the best testimony is given in Mr. Quimby’s own words. The following quotation, from a manuscript dated 1863, was read in the lecture referred to above and afterwards published in The True History of Mental Science, but its real value has been lost sight of owing to the fact that it was quoted in another connection:

“My conversion from disease to health, and the subsequent change from BELIEF in the MEDICAL FACULTY TO ENTIRE DISBELIEF IN IT, AND TO THE KNoWLEDGE of THE TRUTH on WHICH I BASE MY THEoRY.

“Can a theory be found, capable of practice, which can separate truth from error? I undertake to say there is a method of reasoning which, being understood, can separate one from the other. Men never dispute about a fact that can be demonstrated by scientific reasoning. Controversies arise from some idea that has been turned into a false direction, leading to a false position. The basis of my reasoning is this point: that whatever is true to a person, if he cannot prove it, is not necessarily true to another. Therefore, because a person says a thing is no reason that he says true. The greatest evil that follows taking an opinion for a truth is disease. Let medical and religious opinions, which produce so vast an amount of misery, be tested by the rule I have laid down, and it will be seen how much they are founded in truth. For twenty years I have been testing them, and I have failed to find one single principle of truth in either. This is not from any prejudice against the medical faculty; for, when I began to investigate the mind, I was entirely on that side. I was prejudiced in favour of the medical faculty; for I never employed any one outside of the regular faculty, nor took the least particle of quack medicine.

“Some thirty years ago I was very sick, and was considered fast wasting away with consumption. At that time I became so low that it was with difficulty I could walk about. I was all the while under allopathic practice, and I had taken so much calomel that my system was said to be poisoned with it, and I lost many of my teeth from that effect. My symptoms were those of any consumptive, and I had been told that my liver was affected, and my kidneys were diseased, and that my lungs were nearly consumed. I believed all this, from the fact that I had all the symptoms, and could not resist the opinions of the physician while having the proof within me. In this state I was compelled to abandon my business; and, losing all hope, I gave up to die, not that I thought the medical faculty had no wisdom, but that my case was one that could not be cured.

“Having an acquaintance who cured himself by riding horseback, I thought I would try riding in a carriage, as I was too weak to ride horseback. My horse was contrary; and once, when about two miles from home, he stopped at the foot of a long hill, and would not start except as I went by his side. So I was obliged to run nearly the whole distance. Having reached the top of the hill I got into the carriage; and, as I was very much exhausted, I concluded to sit there the balance of the day, if the horse did not start. Like all sickly and nervous people, I could not remain easy in that place; and, seeing a man ploughing, I waited till he had ploughed around a three-acre lot, and got within sound of my voice, when I asked him to start my horse. He did so, and at the time I was so weak I could scarcely lift my whip. But excitement took possession of my senses, and I drove the horse as fast as he could go, up hill and down, till I reached home; and when I got into the stable I felt as strong as I ever did..

“When I commenced to mesmerise, I was not well, according to the medical science, but in my researches I found a remedy for my disease. Here was where I first discovered that mind was matter,[7] and capable of being changed. Also, that disease being a deranged state of mind, the cause I found to exist in our belief. The evidence of this theory I found in myself, for like all others I had believed in medicine. Disease and its power over life, and its curability, are all embraced in our belief. Some believe in various remedies, and others believe that the spirits of the dead prescribe. I have no confidence in the virtue of either. I know that cures have been made in these ways.

I do not deny them. But term the principle on which they are done is the question to solve, for disease can be cured, with or without medicine, on but one principle.[8] I have said I believed in the old practice, and its medicines, the effect of which I had within myself; for, knowing no other way to account for the phenomena, I took it for granted that they were the result of medicine.

“With this mass of evidence staring me in the face, how could I doubt the old practice? Yet, in spite of all my prejudices, I had to yield to a stronger evidence than man’s opinion, and discard the whole theory of medicine, practised by a class of men, some honest, some ignorant, some selfish, and all thinking that the world must be ruled by their opinions.

“Now for my particular experience. I had pains in the back, which they said were caused by my kidneys, which were partially consumed. I also was told that I had ulcers on my lungs. Under this belief, I was miserable enough to be of no account in the world. This was the state I was in when I commenced to mesmerise. On one occasion, when I had my subject asleep, he described the pains I felt in my back (I had never dared to ask him to examine me, for I felt sure that my kidneys were nearly gone), and he placed his hand on the spot where I felt the pain. He then told me that my kidneys were in a very bad state; that one was half consumed, and a piece three inches long had separated from it, and was only connected by a slender thread. This was what I believed to be true, for it agreed with what the doctors told me, and with what I had suffered, for I had not been free from pain for years. My common sense told me that no medicine would ever cure this trouble, and therefore I must suffer till death relieved me. But I asked him if there was any remedy? He replied, ‘Yes, I can put the piece on so it will grow and you will get well.’ At this, I was completely astonished, and knew not what to think. He immediately placed his hands upon me, and said he united the pieces so they would grow. The next day he said they had grown together, and from that day I never have experienced the least pain from them.

“Now what is the secret of the cure? I had not the least doubt but that I was as he described; and if he had said, as I expected that he would, that nothing could be done, I should have died in a year or so. But when he said he could cure me in the way he proposed, I began to think, and I discovered that I had been deceived into a belief that made me sick. The absurdity of his remedies made me doubt the fact that my kidneys were diseased, for he said in two days they were as well as ever. If he saw the first condition, he also saw the last, for in both cases he said he could see. I concluded in the first instance that he read my thoughts, and when he said he could cure me, he drew on his own mind; and his ideas were so absurd that the disease vanished by the absurdity of the cure. This was the first stumbling-block I found in the medical science. I soon ventured to let him examine me further, and in every case he would describe my feelings, but would vary about the amount of disease, and his explanation and remedies always convinced me that I had no such disease, and that my troubles were of my own make.

“At this time I frequently visited the sick with Lucius, by invitation of the attending physician; and the boy examined the patient, and told facts that would astonish everybody, and yet every one of them was believed. For instance, he told a person affected as I had been, only worse, that his lungs looked like a honeycomb, and his liver was covered with ulcers. He then prescribed some simple herb tea and the patient recovered, and the doctor believed the medicine cured him. But I believed that the doctor made the disease, and his faith in the boy made a change in the mind, and the cure followed. Instead of gaining confidence in the doctors, I was forced to the conclusion that their science is false. Man is made up of truth and belief, and if he is deceived into a belief that he has, or is liable to have, a disease, the belief is catching and the effect follows it. I have given the experience of my emancipation from this belief and from confidence in the doctors, so that it may open the eyes of those who stand where I was. I have risen from this belief, and I return to warn my brethren, lest when they are disturbed they shall get into this place of torment prepared by the medical faculty. Having suffered myself, I cannot take advantage of my fellow-men by introducing a new mode of curing disease and prescribing medicine. My theory exposes the hypocrisy of those who undertake to cure in that way. They make ten diseases to one cure, thus bringing a surplus of misery into the world, and shutting out a healthy state of society. They have a monopoly, and no theory that lessens disease can compete with them. When I cure there is one disease the less[9]; but not so when others cure, for the supply of sickness shows that there is more disease on hand than there ever was. Therefore, the labour for health is slow, and the manufactory of disease is greater. The newspapers teem with advertisements of remedies, showing that the supply of disease increases. My theory teaches man to manufacture health; and when people go into this occupation disease will diminish, and those who furnish disease and death will be few and scarce”

Referring to this account of Mr. Quimby’s experience, the lecture on “the true history” continues:

“This account settles many things. First, it gives in detail one of the many experiences by which Mr. Quimby discovered this truth. It shows, also, the practical nature of the man’s mind, and illustrates his wonderful intuitive powers. And the article shows that no one could have written it but the one whose experience it describes; and it shows, too, that what he arrived at was the knowledge that disease is due to an error of belief, to be corrected by the truth. On this basis he practised ever afterward. How could he do otherwise, after making such a discovery? And this discovery was made about forty-five years ago. All these facts can be fully substantiated by consulting certain newspaper files, and certain persons who are familiar with it all. And this theory, that disease is an error of belief to be corrected by the truth, not only formed the basis of ‘a science of health’ which Mr. Quimby introduced, but it is the subject of voluminous manuscripts devoted to the ‘true science of life and happiness,’ and others in which he explained and defended Christ’s sayings, his gospel, and his work. He also wrote upon the true standard of law and of government, and upon other topics. All these writings I have read, being in the confidence of George A. Quimby, the son, who holds them.

“Such is the spirit of the kind of truth that I learned from P. P. Quimby, and the kind that he himself practised; and his spirit of love so opened his soul to the God- power that his works were marvellous. The quick cures that he wrought have not been equalled by any one since his time, so far as I know. Myself and wife have owed our lives to him for nearly twenty-seven years, and to the truth he revealed to us.” Thousands of others could make a similar testimony, but I prefer not to occupy time with relating his cures. The man himself never desired publicity. The truth itself and the good of humanity were the first and last considerations with him. He even had no fixed name for his theory or practice, desiring to be known only by his fruits. He sank the individual wholly in the cause of truth and the good of humanity.

“It is the intention of your speaker to relate this history so as to avoid any appearance of fulsome praise, because the man Quimby would not desire it; and it is my aim only to relate plain facts in a plain manner, and I request you therefore to consider no statement herein as overdrawn. Your attention is called to one important fact, and that is, that the kind of individual I am describing in the person of P. P. Quimby is the kind who can make discoveries of truth, if any one can, that is, a mind of great capabilities, coupled with great humility and extreme unselfishness. This is the kind of instrument that God speaks through, because such a soul is open to the divine inspiration. On the other hand, a selfish soul, who seeks personal aggrandisement, is not open to revelations of much moment, because selfishness always blinds one. The truth does not flourish in such soil.

“P. P. Quimby’s intuitive powers were remarkable. He always told the patient, at the first sitting, what the latter thought was his disease; and, as he was able to do this, he never allowed the patient to tell him anything about his case. Quimby would also tell the patient what the circumstances were which first caused the trouble, explain to him how he fell into his error, and then from this basis prove to him, in many instances, that his state of suffering was an error of mind, and not what he thought it was. Thus his system of treating diseases was really and truly a science, which proved itself. You see, also, from these statements, how he taught his patients to understand, and how persons who went to him for treatment were instructed in the truth, as well as restored to health. In this way some of his patients became especially instructed, as did your speaker.

“Nearly all, in those days, who were willing to try a practitioner outside of the medical schools, had exhausted every means of help within those schools; and, when finally booked for the grave, they would send for or go to Quimby. As he expressed it, they would send for him and for the undertaker at the same time, and the one who got there first would get the case. Consequently, his battle with error, alone and single-handed, was a hard one, especially as in those days there was much less liberality than now.

“Some may desire to ask if, in his practice, he ever in any way used manipulation. I reply that, in treating a patient, after he had finished his explanations, and the silent work, which completed the treatment, he usually rubbed the head two or three minutes, in a brisk manner, for the purpose of letting the patient see that something was done. This was a measure of securing the confidence of the patient at a time when he was starting a new practice, and stood alone in it. I knew him to make many and quick cures at a distance, sometimes with persons he never saw at all. He never considered the touch of the hand as at all necessary, but let it be governed by circumstances, as was done eighteen hundred years ago.

“This truth which P. P. Quimby brought forth, and for years laboured unceasingly to give to the world, and finally laid down his life in its cause—this glorious truth is still blessing us; and it will do so more and more unto the perfect day. It is a revelation of truth that makes us free indeed! And we have only to set aside self-love and self-glory and work earnestly in this cause, by every word and deed of love that opportunity offers, to find ourselves growing gradually into all wisdom and understanding, and out of and away from every ill and every form of unhappiness.”

The lecture closed with the following quotation from Mr. Quimby’s manuscripts:

“Every disease is the invention of man, and has no identity in wisdom; but, to those who believe it, it is a truth.[10] If everything man does not understand were blotted out, what would be left of man? Would he be better or worse, if nine-tenths of all he thinks he knows were blotted out of his mind, and he existed with what is true?

“I contend that he would, as it were, sit on the clouds, and see the world beneath him tormented with ideas that form living errors, whose weight is ignorance. Safe from their power he would not return to the world’s belief for any consideration.

“In a slight degree, this is my case. I sit, as it were, in another world or condition, as far above the belief in disease as the heavens are above the earth, and though safe myself, I grieve for the sins of my fellow-man; and I am reminded of the words of Jesus when he beheld the misery of his countrymen: ‘O Jerusalem! How often would I have gathered thee as a hen gathereth her chickens, but ye would not.’

“I hear this truth now pleading with man to listen to the voice of reason. I know from my own experience with the sick that their troubles are the effect of their own belief; not that their belief is the truth, but their beliefs act upon their minds, bringing them into subjection to their belief, and their troubles are a change that follows.

“Disease is a reality to all mankind; but I do not include myself, because I stand outside of it, where I can see things real to the world and things that are real to wisdom. I know that I can distinguish that which is false from a truth, in religion, or in disease. To me, disease is always false; but, to those who believe it, it is a truth, and the errors of religion the same. Until the world is shaken by investigation, so that the rocks and mountains of religious error are removed and the medical Babylon destroyed, sickness and sorrow will prevail. Feeling as I do, and seeing so many young people go on the broad road to destruction, I can say from the bottom of my soul:

O Priestcraft! fill up the measure of your cups of iniquity, for on your head will come, sooner or later, the sneers and taunts of the people. Your theory will be overthrown by the voice of wisdom that will rouse the men of science, who will battle your error and drive you utterly from the face of the earth. Then there will arise a new science, followed by a new mode of reasoning, which shall teach man that to be wise and well is to unlearn his errors.”

Continuing the sketch of his father’s life already quoted from,[11] Mr. George Quimby says:

“In the year 1859 Mr. Quimby went to Portland, where he remained until the summer of 1865, treating the sick by his peculiar method. It was his custom to converse at length with many of his patients, who became interested in his method of treatment, and to try to unfold to them his ideas.

“Among his earlier patients in Portland were the Misses Ware, daughters of the late Judge Ashur Ware, of the U. S. Court; and they became much interested in ‘the truth,’ as he called it. But the ideas were so new, and his reasoning was so divergent from the popular conceptions, that they found it difficult to follow him or remember all he said; and they suggested to him the propriety of putting into writing the body of his thoughts.

“From that time he began to write out his ideas, which practice he continued until his death, the articles now being in the possession of the writer of this sketch. The original copy he would give to the Misses Ware, and it would be read to him by them; and, if he suggested any alteration, it would be made, after which it would be copied either by the Misses Ware or the writer of this and then re-read to him, that he might see that all was just as he intended it. Not even the most trivial word or the construction of a sentence would be changed without consulting him. He was given to repetition; and it was with difficulty that he could be induced to have a repeated sentence or phrase stricken out, as he would say, ‘If that idea is a good one, and true, it will do no harm to have it in two or three times’ He believed in the hammering process, and of throwing an idea or truth at the reader till it should be firmly fixed in his mind….

“Mr. Quimby, although not belonging to any church or sect, had a deeply religious nature, holding firmly to God as the first cause, and fully believing in immortality and progression after death, though entertaining entirely original conceptions of what death is. He believed that Jesus’ mission was to the sick, and that he performed his cures in a scientific manner, and perfectly understood how he did them. Mr. Quimby was a great reader of the Bible, but put a construction upon it thoroughly in harmony with his train of thought….

“Mr. Quimby’s idea of happiness was to benefit mankind, especially the sick and suffering; and to that end he laboured and gave his life and strength. His patients not only found in him a doctor, but a sympathising friend; and he took the same interest in treating a charity patient that he did a wealthy one. Until the writer went with him as secretary, he kept no accounts and made no charges. He left the keeping of books entirely with his patients; and, although he pretended to have a regular price for visits and attendance he took at settlement whatever the patient chose to pay him.

“The last five years of his life were exceptionally hard. He was overcrowded with patients and greatly overworked, and could not seem to find an opportunity for relaxation. At last nature could no longer bear up under the strain; and, completely tired out, he took to his bed, from which he never rose again. While strong, he had always been able to ward off any disease that would have affected another person; but, when tired out and weak, he no longer had the strength of will or the reasoning powers to combat the sickness which terminated his life.

“An hour before he breathed his last he said to the writer: ‘I am more than ever convinced of the truth of my theory. I am perfectly willing for the change myself, but I know you will all feel badly; but I know that I shall be right here with you, just the same as I have always been. I do not dread the change any more than if I were going on a trip to Philadelphia.’

“His death occurred January 16, 1866, at his residence in Belfast, at the age of sixty-four years, and was the result of too close application to his profession, and of overwork. A more fitting epitaph could not be accorded him than in these words:

“‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’ For, if ever a man did lay down his life for others, that man was Phineas Parkhurst Quimby”

Chapter II. Personal Testimony[12]

IT WAS some time in 1860 that I first heard of Mr. Quimby. He was then practising his method of curing the sick in Portland. My home was a few miles from that city, and we often heard of the wonderful work he was doing. We also heard something about his philosophy; and, as he made war with the prevailing theories of the day, there was a strong prejudice against him in the minds of many people. His patients, however, became his friends, and he gradually won his way into the hearts of the people, especially among those who had received benefit from him, either through his practice or his ideas; and his fame spread more and more.

My own experience was very interesting, and was attended with most happy results. In fact, my first interview with Mr. Quimby marked a turning- point in my life, from which there has been no turning back.

I went to him in May, 1862, as a patient, after six years of great suffering, and as a last resort, after all other methods of cure had utterly failed to bring relief. I had barely faith enough to be willing to go to him, as I had been greatly prejudiced, and still had more of doubt and fear than expectancy of receiving help. But all fear was taken away when I met this good man, with his kindly though searching glance.

The events connected with this first interview are as vivid in mind as those of yesterday. It was like being turned from death to life, and from ignorance of the laws that governed me to the light of truth, in so far as I could understand the meaning of his explanations.

In order to understand the great change which then came into my life, let the reader picture a young girl taken away from school, deprived of all the privileges enjoyed by her associates, shut up for six years in a sickroom, under many kinds of severe and experimental treatment in its worst forms, constantly growing worse, told by her minister that it was the will of God that she should suffer all this torture, seeing the effect of all this trying experience upon the dear ones connected with her,—simply struggling for an existence, and yet seeing no way of escape except through death,—and the reader will have some idea of the state I was in when taken before this strange physician. And, in order to complete the picture, let the reader imagine the inner conflict between all this that was so disheartening and a hope that never wavered, a feeling that there was a way of escape, if it could only be found, a conviction deeper than all this agony of soul and body that the whole situation was wrong, that the torturing treatment was wholly unnecessary, and that it was not God’s will that any one should be kept in such a prison of darkness and suffering.

To have this great hope realised was indeed like the glad escape of a prisoner from the darkest and most miserable dungeon. Yet timid, and expecting to find a man without sympathy, who would attempt some sort of magic with me, it was naturally with much fear and trembling that I made my first visit to his office.

Instead of this, I found a kindly gentleman who met me with such sympathy and gentleness that I immediately felt at ease. He seemed to know at once the attitude of mind of those who applied to him for help, and adapted himself to them accordingly. His years of study of the human mind, of sickness in all its forms, and of the prevailing religious beliefs, gave him the ability to see through the opinions, doubts, and fears of those who sought his aid, and put him in instant sympathy with their mental attitude. He seemed to know that I had come to him feeling that he was a last resort, and with but little faith in him or his mode of treatment. But, instead of telling me that I was not sick, he sat beside me, and explained to me what my sickness was, how I got into the condition, and the way I could have been taken out of it through the right understanding. He seemed to see through the situation from the beginning, and explained the cause and effect so clearly that I could see a little of what he meant. My case was so serious, however, that he did not at first tell me I could be made well. But there was such an effect produced by his explanation that I felt a new hope within me, and began to get well from that day.

He continued to explain my case from day to day, giving me some idea of his theory and its relation to what I had been taught to believe, and sometimes sat silently with me for a short time. I did not understand much that he said, but I felt “the spirit and the life” that came with his words; and I found myself gaining steadily. Some of these pithy sayings of his remained constantly in mind, and were very helpful in preparing the way for a better understanding of his thought, such, for instance, as his remark, that “Whatever we believe, that we create,” or, “Whatever opinion we put into a thing, that we take out of it”

The general effect of these quiet sittings with him was to light up the mind, so that one came in time to understand the troublesome experiences and problems of the past in the light of his clear and convincing explanations. I remember one day especially, when a panorama of past experiences came before me, and I saw just how my trouble had been made; how I had been kept in bondage and enslaved by the doctors and the false opinions that had been given me. From that day the connection was broken with these painful experiences and the terrible practices and experiments which had added so much to my trouble; and I lived in a larger and freer world of thought.

The most vivid remembrance I have of Mr. Quimby is his appearance as he came out of his private office ready for the next patient. That indescribable sense of conviction, of clear-sightedness, of energetic action—that something that made one feel that it would be useless to attempt to cover up or hide anything from him—made an impression never to be forgotten. Even now in recalling it, after thirty-three years, I can feel the thrill of new life which came with his presence and his look. There was something about him that gave one a sense of perfect confidence and ease in his presence,—a feeling that immediately banished all doubts and prejudices, and put one in sympathy with that quiet strength or power by which he wrought his cures.

We took our turn in order, as we happened to come to the office; and, consequently, the reception-room was usually full of people waiting their turn. People were coming to Mr. Quimby from all parts of New England, usually those who had been given up by the best practitioners, and who had been persuaded to try this new mode of treatment as a last resort. Many of these came on crutches or were assisted into the office by some friend; and it was most interesting to note their progress day by day, or the remarkable change produced by a single sitting with the doctor. I remember one woman who had used crutches for twenty years, who walked without them after a few weeks.

Among those in waiting were usually several friends or pupils of Mr. Quimby, who often met in his rooms to talk over the truths he was teaching them. It was a rare privilege for those who were waiting their turn for treatment to listen to these discussions between the strangers and these disciples of his, also to get a sentence now and then from the doctor himself, who would often express some thought that would set us to thinking deeply or talking earnestly.

In this way Mr. Quimby did considerable teaching; and this was his only opportunity to make his ideas known. He did not teach his philosophy in a systematic way in classes or lectures. His personal explanations to each patient, and his readiness to explain his ideas to all who were interested, brought him in close sympathy with all who went to him for help. But further than that he had no time for teaching, as he was always overrun with patients.